The pathway to:

Industrial Decarbonization Commercial Liftoff

The U.S. industrial sector makes products and materials that Americans rely upon and many of these products are inputs to other energy technologies.

These carbon-intensive industrial sectors are facing a critical inflection point, and society is focused on accelerating deep decarbonization.

If the U.S. transport and power sectors decarbonize in line with administration targets and limited abatement occurs in industrials, the share of emissions from all U.S. industrials could rise to 27% of total U.S. CO2e emissions by 2030.vi

Broader U.S. industry progress toward deep decarbonization is at risk of lagging other countries and domestic net-zero targets, although the journey is nuanced by sector.4 Today, industry mostly focuses on a subset of deployable technologies requiring limited investment or process changes, which if fully adopted, would only address ~10% of emissions studied

However, in some sectors, this narrative is changing due to:

Congressional support from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL)5, and the Inflation Reduction Act6 (IRA).

Willing U.S. industry participants could utilize the momentum of the present moment to accelerate the commercialization of decarbonization technologies, respond to rising global demand for clean industrial commodities, and establish the U.S. as a global leader in industrial decarbonization.

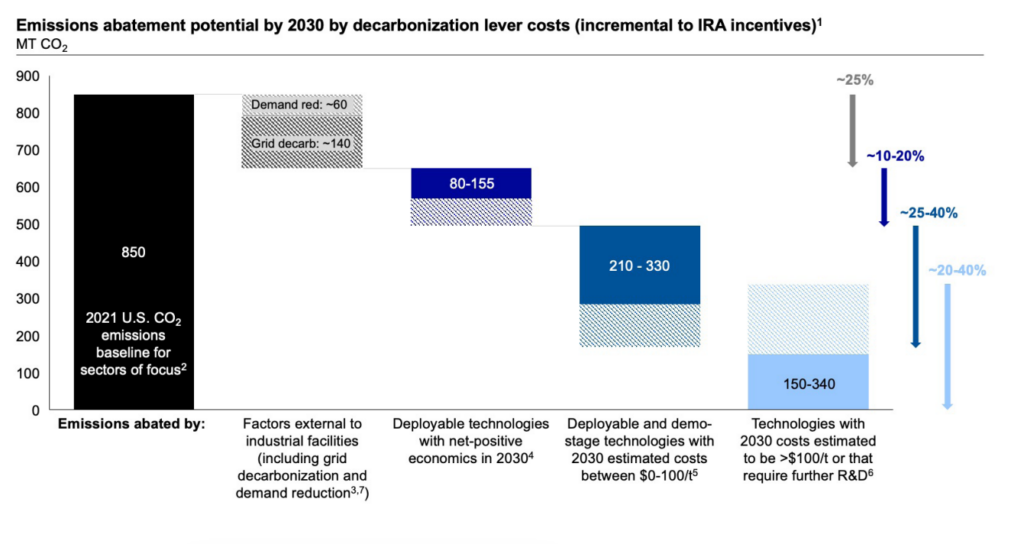

The Liftoff report finds that by 2030, up to 40% of studied emissions7 could be abated with existing net-positive decarbonization levers or external factors.8

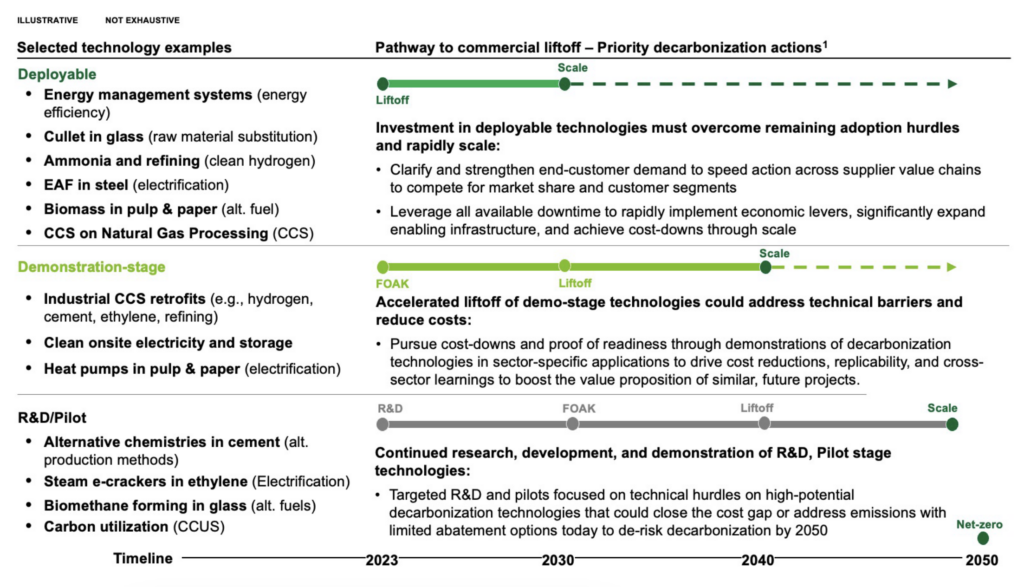

Finally, the Pathway to Commercial Liftoff scenario for industrial decarbonization relies on technologies along the Research, Development, Demonstration, and Deployment (RDD&D) continuum with near-term opportunities for deployable technologies across all sectors studied.

To achieve Liftoff and stay on our path to net-zero, there are key actions for technologies in each stage of commercialization:

Here, “Liftoff” represents the point where solutions become largely self-sustaining markets that do not depend on significant levels of public capital and instead attract private capital with a wide range of risk.

An accelerated pathway to commercial liftoff faces seven major, commercial challenges across all decarbonization levers:

High delivered cost of technology

High complexity to adopt

Limited high-TRL technologies

Lack of enabling infrastructure

Capital flow challenges

Limited demand maturity

Community perception

In partnership with other federal agencies, the Department of Energy (DOE) has the mission, authorities, and funding to begin to address these decarbonization challenges and help implement solutions in concert with the private sector. DOE recently launched a new crosscutting website to consolidate relevant Industrial Technology resources.